Unit II: Pursuing a Future Practice

Christopher Heron, MD; Miranda Huffman, MD, MEd; Kay Kelts, DO; Suzanne Minor, MD, FAAFP; Monica Newton, DO, MPH

Some residents have known since childhood that they wanted to be physicians—even knowing the specialty and type of practice. For others, these dreams emerged slowly over the course of their education. While many big decisions are behind you (like choosing Family Medicine, yay!), you still face important choices about your future career. This unit discusses the basic models of medical practice and key factors for a successful job search. Specifically, we discuss personal preferences, professional goals, basic employment options, payment models and benefits, as well as how to craft a CV, interact with recruiters, interview and negotiate effectively.

Personal Considerations

Personal Considerations

a. Family

The first step is to define your “family.” Family might include a partner, spouse, children, parents, siblings, or close friends. Whoever they are, your “family” consists of those individuals who get a vote in your job search or who factor strongly into that decision. Here is a personal example: my dad wants me to move to my hometown in Ohio but my husband does NOT want to move there (and neither do I). So, while dad is part of my family, he is not part of the “family” that determines my job location. This may lead to occasional stress at family gatherings, but not to the daily stress of being unhappy at home.

Once you have determined who will have a say in your job search, talk to them! Set aside plenty of time for uninterrupted discussions. Your family has most likely sacrificed for you during your training, but they may not have fully disclosed their own hopes and needs. You won’t want to discover this after you sign a contract, as this will make your transition into practice much more challenging. You also don’t want to break a contract, which can be expensive in terms of legal fees, cost of relocating to a new practice, as well as the emotional cost of strained personal and professional relationships. Instead, you will want a situation where everyone “wins” as much as possible.

b. Fun and Fellowship

While it might seem trivial, having your preference of community and activities available to you is also important, especially so if you are moving to a new area. Many of your hobbies, interests and passions may have been postponed as you pursued training. Now will be the time to rekindle some of your other passions, be it scuba diving, salsa dancing, or underwater basket weaving. Alternatively, you may want a particular cultural, religious or other type community with like-minded people. Access to these activities and communities can be important to personal wellness and long-term satisfaction.

There are no right or wrong considerations, except to use the Socratic wisdom, “know thyself,” and to be honest about what is most important to you.

Questions for you and your family to consider may include:

- Where do you want to be in one year, five years, and ten years?

- What parts of the country (or world) are on or off the table?

- What type of community is best for you: big city, suburban, rural, college town?

- Which community aspects are most important? This might include the quality of schools, access to recreational, cultural or religious activities, cost of living, crime rates, ease of transportation, airport availability, housing availability, weather, natural resources or landscape? (Resources include websites like Best Places, Niche and School Digger)

- What salary do you need to pay off any loans and to support your desired standard of living in that area?

- What additional benefits do you and your family need, such as Paid Time Off (PTO), Continuing Medical Education (CME) stipends, health insurance, parental leave, or retirement benefits?

- How many hours a week of work is acceptable to you and your family? Will you work on weekends? If so, how many? Will you take call? If so, how often? Will it be for inpatient, outpatient, obstetrics, emergency department, etc.? Is that sustainable for you and your family?

- How important is job flexibility to your lifestyle and family obligations?

- Do you need access to childcare or specialized educational or social supports?

- Do you have any additional personal goals that need to be considered, such as further training or achievements for you or other family members?

Professional Considerations

Professional Considerations

Professional satisfaction is also very important. It is meaningful to note that almost half of new physicians leave their first position at or before 5 years. While many new graduates cite the location as being the most important factor in their choice, physicians with the longest retention rates prioritized the professional practice environment over the location. In other words, location is very important but may not be the most important factor in finding long-term career satisfaction. Both personal and professional factors together create the highest satisfaction and longevity.

Physicians with the longest retention rates prioritized the professional practice environment over the location.

Professionally, you may desire a full-spectrum practice that is procedure-heavy, and that includes obstetrics and emergency room care; alternatively, you may be exclusively interested in an outpatient clinic or hospital-based practice. Some physicians are interested in pursuing leadership opportunities, community advocacy, medical missions, volunteer service, or teaching opportunities. These are all legitimate considerations from the outset and add to professional satisfaction. If you or family members have any “deal breakers” in terms of your professional practice, it is equally important to be honest about these. Occasionally, you may find tension between what your family wants (40 hrs/week, with no call) and what you want (full-spectrum family medicine, with all the bells and whistles). You may want to talk to professional mentors, including your advisor and program director, as you balance any professional goals with personal and family preferences

a. “Fit"

One of the most important considerations for your future practice is a sense of “fit” with your future colleagues and administration. Understanding and resonating with the mission of the practice is crucial. Additionally, good communication is essential to an effective practice, especially in light of medical, legal, and community changes—and we know that the practice of medicine always involves change! Many family medicine residents have also established good friendships during residency but the transition to independent practice can sometimes feel isolating. Having colleagues you respect and enjoy working with, and who will mentor you as you adjust to independent practice, will make a huge difference. Conversely, your partners can make your professional life challenging if you do not “get along.”

The best way to determine if you fit with the group is to spend time connecting with your potential colleagues and administrators, observing their practice and leadership styles, and asking questions. Your spouse or partner, if you have one, should also be involved as this can add important insights when interacting with your prospective colleagues and their families. Employers at rural facilities may encourage you to work with them for a weekend or week so you can interact with hospital staff and the community. This can be an informal interview, to mutually discern if you are a good fit.

Be aware that administrators are absolutely vital assets to a thriving practice, but can also override your autonomy if you are not on the same page. Do not underestimate the significance of their role. Spend time getting to know them to establish trust. This applies not just to your immediate practice administrator, but also to higher level leaders, particularly if you will be working for a larger institution. If you do not resonate with leadership or disagree with the practice’s mission and vision, you are unlikely to find fulfillment working there.

b. Patient Population

You should also consider your target practice population. You obviously cannot—and should not—discriminate against any subset of patients! You can, however, decide to tailor your practice, such as working with traditionally underserved populations, caring for patients from a particular language or cultural background, providing care to a particular age of patients, such as geriatrics or adolescents. You may also have a specific niche you are passionate about, such as prenatal care, adolescent care, mental health care, obesity or lifestyle medicine, palliative care, sports medicine, substance use disorder treatment, or hepatitis C or HIV treatment. This should be discussed early with prospective practices since the community may not consider your skills to be a particular need, or these may not be service lines that the organization wants to support—and the support of your future practice will be significantly instrumental to you for marketing, recruitment, and clinic operations. Again, do not underestimate the ability of leadership to support or hinder the implementation of your desired practice.

Do not underestimate the ability of leadership to support or hinder the implementation of your desired practice.

c. Scope of Practice

Family physicians may also make decisions about whether to pursue inpatient care, emergency department care, obstetrical care, or perform certain procedures, such as colonoscopies, osteopathic manipulation, or colposcopy. Immediately after residency it is commonly recommended to practice medicine as broadly as possible and then narrow the scope of practice over time. This is because it is generally difficult to resume certain services if there has been a significant gap in time (more than 1 year) since you last provided that service. It’s best to find an initial position that will allow you to do everything you think you might possibly want to do during the course of your career. If, however, you are certain you don’t want a specific type of practice or particular lifestyle, it may be advisable to focus on building your preferred practice and decline other services, even if you trained in them. This decision requires careful discernment of what you enjoy and value professionally, what risks you are willing to take, and what type of commitment or sacrifice you and your family are willing to make. Obviously, covering the emergency department, inpatient medicine or obstetrical care will have an impact on your home life.

i INPATIENT

Some practices are designed with both outpatient and inpatient care, especially physician-owned practices or smaller facilities which have a hospital and clinic as part of the same system. Other inpatient options include a career as a hospitalist, which is generally shift work and may include intensive care. There is a big difference between rounding with a team to cover a larger group of patients and seeing a handful of your hospitalized continuity patients before you begin your clinic day. You should assess your hospital knowledge and skills and, if needed, brush up on any deficits based on expected acuity level or procedures that are expected of the position. Additionally, even though you have a national provider identifier (NPI) number, a state medical license and board certification, be aware that you still have to seek “privileges” to work in a particular hospital. In other words, while you can see patients and prescribe medications on an outpatient basis, you cannot start admitting patients, writing orders, or performing procedures in any given hospital. Most hospitals will verify through a medical staff committee that you are a physician in good standing, and that you have the needed procedural and practice qualifications for the scope of practice you are requesting. You will need your procedure log from residency in order to obtain privileges, so keep it handy! Medical staff also will want to ensure you don’t have major legal, medical malpractice, or untreated mental health or substance use disorders. Hospital privileges will have to be periodically reapproved by the medical staff committee.

Questions about inpatient service to consider:

- What does the typical call schedule look like?

- Are there back-up plans in place? What happens if someone is on parental leave or leaves the practice unexpectedly?

- What is the average number of admissions per shift? How many patients will need to be rounded on and what is their acuity?

- Is there adequate imaging, a laboratory and a blood bank available?

- What specialty care is available? Is there an intensivist?

- Will you cover ICU patients?

- Will you be expected to perform hospital procedures, such as rapid sequence intubations, chest tubes, central lines, arterial lines, paracentesis, thoracenteses, incision and drainage, joint aspirations?

- Will you cover women’s health procedures, such as Dilation and Curettage(D&C)?

- If not a tertiary center, what is the transport plan? Is it timely, especially for urgent situations?

- Will you work with APPs, residents or students?

ii.EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Some physicians also enjoy emergency department (ED) care. Some work full time in emergency rooms, while others cover the ED as part of their regular responsibilities in a rural facility. Emergency medicine is often very rewarding and interesting, but naturally involves risk and can be demanding at times. Working at larger or busier emergency departments typically involves 8 or 12 hour shifts and, depending on the arrangement, can be somewhat flexible about scheduling. Rural emergency department call schedules are often integrated with other professional responsibilities, such as clinic. It can involve covering 24 or 48 hour weekend shifts, or 24 hour shifts throughout the week, which can vary from slow to very busy.

On the one hand, you will need to consider if a lower number of longer shifts will allow you to maintain adequate skills. On the other hand, you need to consider how this affects your personal life, such as family life and sleep habits, and whether you can adjust to canceling or delaying scheduled clinic visits when emergencies come in.

Questions about emergency department service to consider:

- What is the schedule and how many ED patients will you see per 12 hour or 24 hour shift?

- What is the longest call period you will be expected to work? How often will you cover call?

- Are you comfortable with the high acuity of ER, including the risk?

- What resources does the facility have for urgent situations? Is it a Level 1-4 trauma center? Is there an adequate blood bank, CT scanner or urgent laboratory testing?

- What level of training does the staff have? Are the staff adequately trained in coding patients, intubations, and trauma management? Are there specialists available for time-bound services like revascularization?

- What is the transfer plan and accessibility to transportation?

- If you have patients scheduled and are called to an emergen-cy, will your patients be rescheduled or will another physician cover?

iii. OBSTETRICS

Coverage of obstetrics, including labor and delivery, is expected or encouraged in some rural facilities, whereas being able to obtain hospital privileges as a family physician varies in larger facilities. Perhaps most important, you need to be sure you will find joy in obstetrics and that it will fit into a healthy lifestyle for you. You also need to assure you can practice obstetrics with continued competency. Generally, physicians should perform at least 40 deliveries a year to maintain these skills, but a hospital that only performs 40 deliveries a year is unlikely to have adequately experienced staff to manage antepartum and postpartum care, as well as care for newborns. In other words, you won’t want to be the only person performing obstetrics in the hospital—and you would essentially be on-call 24/7 if you were!

Most rural sites integrate obstetrical care into other professional activities—and you may have to cancel or delay clinic visits to attend a delivery. This can be frustrating for some physicians, although many patients in rural areas accept this, recognizing the value of having local obstetrical options. Your decision will need to be based on the call schedule, average number of expected deliveries per week or month, nursing staff competence, anesthesia availability, and the operative delivery options. You will also want to know the policies and staffing for management of preeclampsia, preterm labor, twin deliveries, primary and repeat C-sections, Trial of Labor After Cesarean (TOLAC) Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC), surgical backup for complicated patients, and about management and transfer of patients, including newborns. Finally, you will want to understand any physician back-up plans if you will be covering both obstetrics and the emergency department.

Questions about obstetric service to consider:

- Who covers obstetrical calls and laboring patients on weekends/after hours? Does the local culture dictate that the primary care physician take these calls?

- How trained and experienced are local nursing staff? Are they able to do vaginal exams, check for ruptured membranes, and understand a Fetal Heart Monitoring (FHM) strip? Do they go through Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) training?

- Is continuous FHM available? Is it electronic so that you can watch the strips from your office or home?

- Are there competent anesthesiologists or Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs)?

- What is the local primary c-section rate? Is VBAC performed and, if so, what are policies for who remains “in house”?

- What is the target time between you “calling” a stat C-section until the baby is delivered? Are they achieving this target?

- Who double-scrubs the C-sections or cares for complicated newborns and resuscitation efforts, if the primary physician is busy addressing maternal health?

- What transfer options are available and how quickly are they available?

- Is there an adequate blood bank, comprehensive plans for massive transfusion, IV magnesium, IV glucose for neonates, etc?

iv. PROCEDURES

All family physicians are expected to have some basic procedural skills (not requiring documentation), such as pelvic exams, skin tag removals, or trimming calluses. However, due to regional culture and local practices, some specialized procedures are often performed by other types of physicians. You may be very well-trained to do the same procedure, and with adequate numbers performed during residency, but simply “not allowed” to perform them. Examples might include obstetrical care (vaginal deliveries, operative deliveries, or C-sections), cervical procedures (colposcopies or Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedures [LEEPs]), or screening endoscopy.

Some of these restrictions are due to local perceptions about the appropriate scope of family medicine. Specialists may also see these procedures as necessary for their own financial stability or to maintain their own skills. Hospital policies and local medical culture are not easily changed, so you won’t want to go in expecting to “change their minds.” If the ability to perform a procedure is essential to you, ask for written assurance in your contract to perform that procedure; otherwise, look for another practice that allows this professional satisfaction.

If the ability to perform a procedure is essential to you, ask for written assurance in your contract to per-form the procedure.

As discussed previously, before performing any major procedures, you will need to obtain privileges. You may be asked to provide documentation that you have completed a certain minimum number so you must save copies of your procedure log during residency.

You may need it for your first position, after residency, and possibly again later in your career. The required minimal number of procedures will vary between healthcare institutions, as well as with national and local expectations. Some major procedures like C-sections may also require direct observation by local physicians until they are comfortable “signing off” on your performance. This should not be seen as an affront to your training or skills, but rather as a way of protecting patients and the hospital’s liability from physicians who do lack adequate procedural skill.

d. Summary

We have reviewed some practice-specific questions above. Here are some additional questions and tools to help with your decision:

General Professional Questions:

- What is the need for family physicians in the community?

- What type of patient population interests you most?

- What type of work and setting do you want to practice in?

- What type of schedule do you want? Do you need an administration day?

- Do you want to be employed, join a physician-led group, start your own practice, be self-employed, join a group practice, or something else altogether?

- In what type of work environment and culture do you tend to thrive?

- What type of boss or employer do you prefer to work for, if any?

- How big do you want the group you work with to be—if you want to work with a group at all? Do all of the members of the group need to be family physicians (as opposed to other specialties)? Will call be shared equally? Do you want to work with advanced practice providers?

- If joining an organization, what is the overall culture of the organization? Do you share a similar “ethos” in how you approach colleagues, patients, and staff?

- If joining an organization or physician group, are they approachable if you have questions or concerns? Will they listen to your ideas and respect your opinions? What are the various kinds of personalities involved and do they respect each other? Are you comfortable with their practice style and competency? Are there major personal or professional stresses that might result in you working more hours or absorbing a patient panel if someone resigns?

- What type of support staff do you need — MAs, RNs, LPNs, social workers, psychologists, pharmacists, case managers, etc.?

- Do you want to have learners working with you — medical students, residents, or fellows? Do you want learners to be a core part of practice or just occasionally?

- Do you want to have opportunities for leadership within your organization or within your broader community?

- Do you have specific professional goals you want to achieve?

The Happy MD Academy: Ideal Physician Job Search Form

There is a huge demand for family physicians and you will be a valuable asset wherever you go! They are looking for someone with a heart to serve and are hoping you will stay with their practice long term. Be confident, know your worth, and advocate for your needs and goals so that you are truly satisfied in your career. We will discuss practical tips under Negotiation.

Be confident, know your worth, and advocate for your needs and goals.

However, be aware that some locations do not have extensive financial or logistical resources. Be mindful and respectful when advocating for particularly unusual types of procedures, practices, or contractual benefits. As with any “relationship,” it’s a two-way street and a seemingly huge “win” upfront could lead to frustration from leadership or the local medical community. Conversely, don’t consider a position just because of a general desire to help or a sense of obligation and don't “lead them on” if you are genuinely not interested. Honesty, confidence, and integrity are key.

Types of Medical Practice Models

Types of Medical Practice Models

Your choice of practice model is also a very important decision that can impact your compensation, autonomy, and job satisfaction. There are many types of practices, including solo, small or large group, single or multiple specialty, hospital or healthcare institution, health maintenance organization-based (HMO), outpatient vs hospitalist (or both), direct primary care, contracting, locums tenens, governmental (including military), and international service. These types of practices are addressed in more detail in the following unit. In this section, however, we cover some of the most common categories in general: starting your own practice, buying or buying into a practice, becoming employed, joining an affiliated practice with a Provider Service Agreement (PSA), and independent contracting.

a. Practice trends

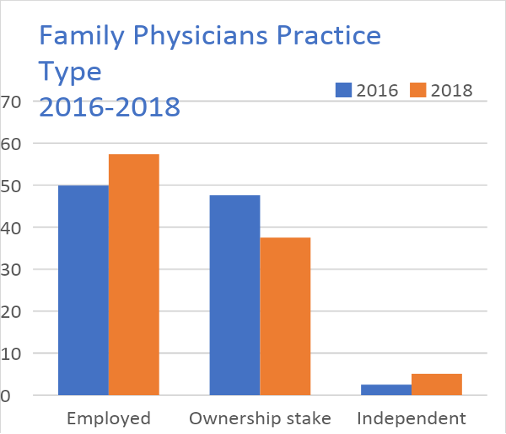

As discussed in the Introduction to this Handbook, the days of exchanging medical care for chickens is over, and physicians owning their own medical practices, as businesses, has also decreased. Instead, over the last three decades, physicians have shifted towards employed positions in healthcare organizations. In fact, a landmark shift was reached in 2018 when slightly more physicians of all specialties were employed (47.5%) than had ownership stakes (47.4%) in their practices!

Family physicians are even more likely than other specialties to be employed: 57.4% are employed versus 37.5% who own their own practices, and it is even more pronounced in some states. The percentage of family physicians who work full-time as independent contractors (such as locum tenens) has only slightly increased. Women physicians and younger physicians tend to be less likely to own their practices than their older male colleagues. In 2018, ownership was 54% among physicians age 55 and older, but only 25% among physicians under the age of 40.

Figure 1: 2018 AMA Benchmark study

There are many reasons for these trends. Some physicians feel limited by their lack of business knowledge and skills. Parents may believe the additional time required for practice management and administration is not easily compatible with their family life, or other goals and needs. New physicians may be hesitant to take on additional financial risk, given student loans and often a new home mortgage. In contrast, there is security and stability in a contract, a predictable salary, and employment benefits. Finally, there is ever-increasing complexity in healthcare delivery, including compliance with state and federal regulations, insurance requirements, and quality reporting. Managing compliance and reporting operations does not appeal to some family physicians. For more information on practice trends, advantages and disadvantages, see this article: The Physician Employment Trend: What you need to know by Travis Singleton and Phillip Miller (Fam Pract Manag. 2015 Jul-Aug;22(4):11-15.)

b. Establishing your own practice

For some physicians, starting a private practice “from scratch” is appealing: it can provide more autonomy, lead to financial success, and has the lowest physician turnover. It also has the most responsibility and risk. While general advice is provided below, getting help from a healthcare lawyer and the AAFP, or your state chapter, is critical to implementing best practices. Additionally, talk to other physicians who have their own practices before fully committing.

For some physicians, starting a private practice “from scratch” is appealing: it can provide more autonomy, lead to financial success and has the lowest physician turnover.

When establishing your own practice, you may need to take out a loan, rent or buy property, set up the clinic rooms, hire, manage and pay your office staff, meet all state and federal regulations, and develop contractual partnerships with commercial laboratories, radiology departments, and other ancillary testing facilities. You will likely need to purchase some lab and radiology equipment, and, depending on their complexity, hire qualified staff to operate them. You will also need to avoid credentialing pitfalls with health care agencies and healthcare payers (insurance companies), manage or outsource billing and collections, and learn the complexities of revenue cycle management. Detailed information on these topics is available elsewhere in this Handbook.

In addition, you will need to build your own patient panel. Advertising and managing social media and online reviews will take time and energy. You will need to consider how to cover patient calls and refill requests when on vacation and whether you will take after-hour calls from your patients. Finally, income may be sparse at first with initial high overhead costs and business loan payments. That said, while it does involve a fair amount of work to establish your own practice—and it does carry risk—many physicians are very fulfilled in this model.

c. Buying (or buying into) an established practice

Instead of starting from scratch, another option is to buy an already established practice or to buy a retiring physician’s practice. There are a number of physicians who own their own practices and are nearing retirement; many are seeking new physicians to buy their practices. Buying a practice can make the initial set-up much easier, because it will likely already have an existing patient panel, be compliant with local health codes, and have necessary equipment, such as exam tables, stools, weighing machines, wall-mounted otoscopes, a medical refrigerator, an electronic health record system, and possibly other procedural, laboratory and radiology equipment.

There is no rule of thumb when it comes to the cost of buying an established practice. There can be a price-per-patient-chart or a motivated retiring physician might sell the entire practice for a flat price. Retiring physicians may be eager to sell their practice and enjoy retirement, but this is also an expensive piece of equity they own, and they won’t want to sell at a loss. However it is priced, it is an investment with inherent risks and subject to market fluctuations. Some retiring physicians may also continue partial ownership of the business or stay in practice part time for several years, which may be ideal while you slowly assume responsibility and ownership of the practice. As long as you have a well described contractual agreement, this arrangement can work well, but it should not be pursued without formal terms and legal review, no matter how well you trust the retiring physician. Without well-written contract, too many misunderstandings can occur, leading to serious professional rifts and expensive legal action.

As long as you have a well described contractual agreement, this arrangement can work well, but it should not be pursued without formal terms and legal review, no matter how well you trust the retiring physician.

Other practices allow new physicians to slowly “buy into” an established practice jointly owned by other physicians. They are often interested in new partners, since this creates patient panel or service line growth and new income and stability for the practice when physicians retire or move. New physicians usually are required to work for several years before becoming eligible to be a joint owner to assure that you are committed to the practice and a good partner. You will also be deciding if you want to stay long-term with the group. During this time, you may make a lower income: either flat salary or salary plus limited productivity. (See “Physician Compensation Models.”) Meanwhile, the partners who own the practice earn the primary dividends of your productivity—as well as their own. This is a “sweat equity” method and may initially reduce your available income. However, after some number of years of service, you then buy a share of the business, which will ultimately generate a monthly dividend for you and, when you retire, your share of the business can be sold to a new physician partner.

This arrangement works well if all owners share the same vision and commitment to hard work, and the terms about reimbursement and ownership are clear to everyone. However, it can also lead to resentment if some physicians see fewer patients or generate less income for the practice. There can be differences of opinion about how to invest, what equipment to purchase, how many partners to include, how many staff to employ, or whether to offer particular service lines, like obstetrics or various other procedures. Additionally, if current trends continue, it’s possible that new physicians will not want to buy your share of the practice when you retire. However, you should seriously consider the short-term and long-term benefits of owning a practice or a share of a practice, as well as what degree of risk you are willing to assume. Consulting with an attorney, determining the value of buying in, and estimating what the “buyout” might be at the time of your retirement are all crucial considerations and will vary with location and the nuances of each particular practice.

Before you start or buy into a practice you should consider:

- The reputations of the other physicians and the practice in the community and whether you can work with them long-term

- The current financial condition of the practice, including debt, liability, and collection ratios (which is covered later)

- The market potential, including the ratio of physicians to local population, and demographic trends that impact market potential, ie, a growing area with lots of new families, a retiree community, etc.

- Any liabilities of the practice or partners (malpractice claims, audit judgements, etc.)

- How long the practice physicians have been with the practice and when they intend to retire. Are they having you buy in so they can all retire and you will now own a million dollar property with no ability to cover the patient population? How will they exit practice and will they still have control over capital expenditures after they retire?

- The age and usability of technology, including computer software and electronic health records (EHRs)

- The value and condition of current assets like furniture, fixtures, equipment

d. Physician employment

Employment means a healthcare system or practice directly hires a physician through a contract which clearly stipulates compensation, benefits, and malpractice coverage. The employer typically hires and pays (or contracts with outside companies) non-physician staff, such as nurses, medical assistants, receptionists, billing and coding experts, office managers, human resource managers, information technology resources, janitors and waste management. They also own or rent the building and any medical equipment. Although physician usually have input and leadership roles, it is the employer who generally directs the practice operations, including setting the schedule for the number of patients or procedures, setting the number of shifts, or generating a particular goal for physician productivity.

Besides compensation, most employment contracts include important benefits, including PTO; health, disability, and malpractice insurances; and CME stipends. Some contracts may also have loan repayment options, bonuses, and/or moving stipends. While you can advocate for changes to the contract, you generally have less autonomy than you might in a privately-owned practice, and a contract is legally binding and can only be modified by a mutually agreed upon amendment. Breaking a contract or failing to meet contractual obligations may carry significant financial or legal penalties, or result in termination.

Generally speaking, there is less financial risk in being an employee, as you do not cover overhead for the practice and you have a clear contract with legally binding compensation and benefits. However, employers don’t necessarily have an effective strategic business plan to help you recruit and retain patients, and you may still be responsible for maintaining your productivity. Talking with other physicians in the system will help you understand the various dynamics of being employed with that healthcare entity, including benefits, surprises and disappointments.

e. Provider service agreements

Provider Service Agreements (PSAs), in their simplest form, align healthcare institutions and physicians in payment arrangements that fall just short of full employment — it is an “employment-like” option. The physician is not technically employed by the healthcare system and maintains some control over the clinical and operational workings of the group, clinic or practice. A common example includes hospitalist groups, where the group is contracted with the hospital for coverage. In addition to a hybrid model, there are three types of PSAs: Traditional PSA, Global Payment PSA, and Practice Management Arrangement). While there are differences between each of these three models, they all generally allow physicians or physician groups to maintain some control and, further, physicians within the group can negotiate the price of their services. There are varying models of paying for overhead (either paid entirely by the healthcare institution, paid by a portion of the compensation provided to physicians/physician groups, or shared between both). Overhead includes the cost of non-physician staff, billing and collection services, administrative costs, equipment, etc.

f. Independent contracting

Most residents are familiar with the concept of moonlighting, but may not have fully considered the implications of independent contracting. In this model, you are self-employed and you contract yourself directly with a locum tenens company or with a healthcare organization. You agree to work by the hour, the shift, the week, or even by the year. Alternatively, you might be paid by the number of patients you care for, such as with telemedicine. You are usually paid at a particular rate per hour/day or at a flat fee. Travel costs and lodging may also be covered in some situations. There are no traditional benefits, such as health insurance, CME or malpractice coverage; you will also have to cover the costs of maintaining licensing and board certification. And you must pay quarterly self-employment taxes on your earnings. The organization you work for generally has no obligation to supply you with an adequate number of shifts and, conversely, you generally have no obligation to work any given number of shifts (although they may establish a bare minimum). There are a few other models of independent contracting, such as being a director of a nursing home, which may involve a longer commitment. Some physicians will work in the same location for many years while remaining self-employed in order to retain the independence of this model. Because you do not have any overhead, there is no financial risk as long as you can continue to find work and remember to pay your own taxes. Many physicians are very happy with independent contracting because of the autonomy and flexibility it provides. More detailed information about this model is available elsewhere in the Handbook

Many physicians are very happy with independent contracting because of the autonomy and flexibility it provides.

g. Academic medicine

Academic family physicians may be hospital employees (especially if they work in a community-based residency) or university employees (especially if they work for a medical school). Some academic organizations have a separate company that exists just to employ teaching physicians and bill for their work. This often allows physicians to have a better benefit portfolio than hospital or university employees. However, university employees may enjoy tuition or other state-employee benefits. Academic medicine generally brings in a lower salary than other employment models, but may have improved healthcare and retirement benefits. Most physicians who choose academic medicine do so because of their interest in training the next generation of physicians and/or performing research to contribute to our knowledge of the practice of medicine. More information is available in the following Unit.

h. Comparing the practice models

The pros and cons of independent practice, ownership in group practice, employment, and partial employment merit careful consideration. You should consider your comfort level with each type, including the upfront financial investment, level of risk, desire for autonomy, collegiality with other physicians, and interest in practice management. The various models are presented in more detail in the following unit. You can also take this quiz to see which practice style might be best for you:

This table briefly outlines some of the important practice model considerations:

Basics of Contracts

Basics of Contracts

Now that you are familiar with some different types of practice models and employment arrangements, we will cover some basic physician contract categories to expect, whether from a physician-owned practice or from a healthcare organization. The main categories include physician compensation, work expectations, benefits, medical liability coverage, loan forgiveness, restrictive covenants and termination clauses. Contracts for independent contracting will vary significantly, as they tend not to include benefits, but should still cover a number of other aspects, as well as hidden contractual clauses that can be consequential.

a. Compensation Plans

Compensation is not always straightforward. How you are paid and how much you are paid depends on the location and type of practice you are entering. Compensation itself varies significantly by region and you are unlikely to negotiate much outside of the “going rates” for that area. And, while you may be able to negotiate on the salary or reimbursement for productivity, you generally cannot negotiate on the type of compensation plan itself.

Here are some common compensation plans:

- i. Hourly or Per Diem: Independent contracting jobs will usually pay you per hour, per day (per diem), or per patient encounter for your coverage of all patient care responsibilities assigned to that position. For time-based payment, you will still get paid the hourly or daily rate—whether you are swamped or even if there are no patients at all. Telemedicine contracting can be a flat rate per patient encounter, regardless of time or complexity. There are generally no benefits, although your malpractice and/or travel and lodging costs might be covered. You will need to remember to set aside and pay estimated taxes quarterly.

- ii. Base Salary: This applies to employed physicians in large HMOs, large group practices, and those in academic settings. It's a very straightforward model. No matter how many hours you work, how many patients you see, how many procedures you do, or how good your outcomes are, you receive the same salary every paycheck. Some may offer incentives or bonuses if the practice is successful, which should be made clear in the contract. Incentives are generally paid annually but can also be paid in other time frames, i.e., quarterly. A base salary, with or without incentives, is a common model for new physicians, and provides a predictable salary.

- iii. Production or Productivity-based Compensation Plans: Physicians may be compensated based on the amount of revenue generated from their work. Most commonly, there is a base salary, plus additional compensation for more work beyond a minimum. Essentially, the more you work, the more you are paid. There are a variety of ways of providing this additional compensation. It can be based on how many patients you see or procedures you perform, which is calculated from fee-for-service CPT codes into “work Relative Value Units” or wRVUs. These calculations are discussed in more detail later in this Handbook. You can also be reimbursed based on resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS), on charges, or on net or gross collections. These various ways of determining productivity could make a big difference to you. For example, wRVUs involve the number of patients you saw, regardless of whether the practice gets paid for those visits in the end. If an insurance company or a patient declines to pay for the service, you still get paid for your work (although the practice as a whole would lose money for that visit). If you were paid based on collections, however, your bottom line would be affected by the effectiveness of your billing department with insurance companies and patients. You will need to understand exactly how compensation works with a given contract and ask questions until it makes complete sense. You will also want to understand compensation for other services, like procedures and obstetrics.

- iv. Productivity and Quality-based Combined Compensation Plans: As payment methods for patient care move toward “value-based care,” some plans also incentivize physicians based on patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, and quality improvement utilization. In other words, the physician receives additional income for meeting particular goals of care for the patient population or practice. Usually, the practice as a whole agrees with healthcare payers about which targets it wants to achieve; for example, to improve vaccination rates, cancer screenings, keeping hospital admission rates low, etc. Healthcare payers pay more to the practice when these targets are met and this additional payment is distributed among all the providers in the practice.

- v.Capitation and Capitation Plus Productivity Plans: Capitation is a prepaid set amount of payment per patient, per period of time. This payment (or healthcare premium) comes from the patient’s healthcare payer and is paid to the physician’s practice on a recurring basis. The patient is locked into receiving all healthcare from that facility. It can be for outpatient care only or for a combination of outpatient and inpatient care. No matter how many times the patient sees the physician or what tests are ordered, it all comes out of the total sum provided to the practice. In other words, if the patient needs more care, beyond the total capitation amount, the practice must cover those additional costs—not the insurance payer. This could be financially beneficial or risky, depending on the patient panel and agreement patterns. This type of plan is most common in certain HMO markets, including the Northeast, California, and Minnesota.

- vi.Partnerships or Equal Shares: As a partial owner of a medical practice, after all business expenses of the practice are paid, you and your colleagues divide the income. As with the other types of compensation, you should receive a very specific contractual explanation of how the income is distributed.

Be aware that contracts may change compensation models after a few years of employment. For example, a newly employed physician may begin at a base salary for the first several years, with or without some reimbursement for productivity. This may be followed by reimbursement at a higher rate for productivity, but without a base salary. This model allows the physician to build up a practice with the financial security of a stable salary. Then, once sustainable patient panel is obtained, productivity incentivizes the physician to see those patients and continue building the practice. While it might seem risky, this model can actually be more financially beneficial, since the productivity reimbursement is often higher than a base salary. There may be minimums set by the practice and various benchmarks to achieve.

b. Work Expectations

Your professional responsibilities should be carefully described in your contract:

- Whether you will be full or part time

- The work days and hours per week

- The minimum expectations for number of patients or procedures (or RVUs)

- Any shared call responsibilities and, specifically, what is involved while on call

- Any administrative, leadership, or teaching responsibilities, as well as time allotted for these

- To whom you will report

- Who reports to you and who you legally oversee [staff, advanced practice providers (APPs)]

- Office policies and procedures, such as how long you have to sign off charts or complete other paperwork

- Licensing, board certification, and any other certifications you must maintain (such as ACLS, PALS, NRP, ALSO, ATLS, etc.) and who pays for those

c. Benefits

Benefits are another important compensation feature to consider carefully. The first benefit everyone wants to know about is Paid Time Off (PTO). However, you should also consider:

- Life and disability insurance plans

- Malpractice coverages

- Health benefits for you and your family

- Employer-sponsored retirement plans

- CME time and financial reimbursement

- State licensing

- DEA registration feesProfessional organization fees (sometimes covered separately from your CME)

Paid Time Off (PTO) is often standardized for the practice and typically merges vacation and sick time. The practice is unlikely to expand this for you without some compelling reason, or without a decrease in other benefits to make up for the lost productivity.

Maternity and paternity leave is required by law under the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, but it does not apply to smaller practices; you should ask about this directly. Leave of absence is usually unpaid, although you may be able to access short-term disability benefits for some of the time. You may also want to inquire about protected time to be able to pump when feeding an infant, if this applies to you. Life, disability, and health insurances, with or without vision and dental coverage, often have several options for you to choose from, based on your preferences and situation.

You should carefully consider if you would benefit most from a Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan, versus a High Deductible Health Plan with a Health Savings Account. These are discussed in more detail in the “Financial Wellness” section. In addition to salary and incentives, your total financial compensation for a prospective position should factor in a comparison of PTO and the other benefits for you and/or your family.

d. Student Loan Repayment Options

Sometimes student loan repayment options can be worked into your contract, particularly for those going to underserved areas. Usually these come as bonuses expressly for loan repayment and will come in yearly allotments for a particular number of years worked. You will have to pay income taxes on these bonuses, and you may owe the full amount back to your employer if you leave before your contract period is over, even if you worked for several years. Outside of your contract, there are also national or state loan repayment options which can be found in the “Financial Wellness” section.

e. Sign on Bonus and Relocation Expenses

Many contracts will include a sign-on bonus, either as a flat payment or distributed yearly. While you receive these payments immediately in most cases, if the contract is not fulfilled, these bonuses often must be repaid (sometimes with penalties). Many employers also cover moving expenses, up to a certain amount. Unless offered a flat fee, receipts are often needed for reimbursement, i.e., for packing, driving and temporary storage expenses.

f. Termination and resignation (leaving)

Some final important considerations in contracts include the length of contract, what amount of sign-on bonus will need to be repaid with early contract termination, length of time you will need to continue working after giving notice of resignation (leaving for any reason), termination clauses, and restrictive covenants (non-compete clauses).

Contracts can vary significantly in length, but initial contracts are typically for 1-3 years. If you advocate for an unusually short contract, it may signal to the employer that you are “on the fence” about committing to work at that location. However, remember that a lot can change in a short time and shorter contracts may allow you more flexibility if you’re less certain about a practice. If you are buying into a practice, you might only have a 1- or2-year contract so you can mutually decide if you are a good fit for the organization.

Most employers will require at least a 2-week written notice of resignation, but for physicians it is more typically 90 to 180 days, since it takes time to replace physicians and to shift patients to a new provider. If you do leave a practice, you may need to repay part of your sign on bonus. Furthermore, as loan forgiveness can involve a year-to-year ratio, you will want to be aware of what happens to loans for the part of the year that you worked for the practice. You will also want to know whether loan forgiveness would continue for the remainder of your work time or stop at the time of resignation.

Termination is never something anyone wants to think about, but under certain circumstances, physicians can be “fired” by their employer. Some reasons are obvious, such as gross negligence, substance use affecting work performance, sexual misconduct, grossly inappropriate prescribing of controlled substances, felony, etc. Others are less obvious, but may include chronically incomplete paperwork, consistent errors in coding, and not keeping up with licensing or board certification requirements.

Termination can be “with cause” or “without cause.” With cause means that a specific reason is given for the termination and has much more serious implications for future employment opportunities. It is recommended to have the contract reflect a reciprocal “termination without cause,” so that either party can revoke the contract without a specific reason. Additionally, you should try to negotiate a provision that requires the employer to give a warning first, prior to termination, which gives the opportunity for remediation first. Physicians are sometimes asked to resign instead of being terminated, because of concerns for future employment and so that the physician does not press charges against the employer for wrongful termination. If the state professional board may already be involved, this may affect the physician's “permanent record,” regardless of whether the physician resigns or is terminated.

g. Restrictive Covenants

Restrictive covenants (or non-compete clauses) are placed by most employers to protect their business from competition or “stealing patients.” It is often specified by distance and time. For example, if you resign or are terminated by your employer, the contract could state that you cannot work within 10 miles of your original practice for 2 years. However, they may also specify that you cannot work within 10 miles of any of their practice locations for 2 years, which may significantly limit where you can practice if they own multiple locations. When you leave a practice, you are also not allowed to recruit patients to your new practice, although you may be permitted to disclose the location of your future practice. This can cause considerable stress in finding a new position within a reasonable driving distance of your current home. While you can try to negotiate out of a restrictive covenant, this is generally unsuccessful, especially in larger organizations. However, it may be possible to negotiate the distance, ie, 10 miles instead of 50 miles. Non-compete clauses may not always be en forceable, but if you intend to violate one, you should consult a healthcare attorney to avoid legal penalties. Additionally, while it is not considered a restrictive covenant, most places will not allow you to recruit your patient population to your new practice. You are sometimes allowed to informally inform them about your plans, but you generally cannot encourage them to establish with you elsewhere.

Professional Liability Coverage (Malpractice Insurance)

Professional Liability Coverage

Practicing medicine comes with great reward, yet considerable risk. Obtaining appropriate insurance coverage assists in mitigating some of that risk, professionally and financially. It also protects a physician’s personal assets since defending a medical professional negligence claim can result in a substantial financial burden. Damages paid out can be high. Meanwhile, time and expense to investigate and defend claims are also considerable and costly. Moreover, physicians have a responsibility to carry malpractice insurance to protect themselves, their practice and their patients. Liability coverage is also required to obtain hospital privileges since this protects the hospital, especially given the overall increased risk compared to outpatient medicine.

Most contracts will provide liability coverage with a company of their choice and you will have little ability to change the specifics of the policy, which typically lasts 1 year, with assumed renewal. However, if you are going to contract independently, you will need to purchase your own coverage. The cost of malpractice insurance is based on the amount of time you spend in patient care per year, the type of work you do (eg, obstetrics and emergency room care is more risky than office-based practice), and the maximum amount of financial coverage you wish to have. Most insurance policies fall into two categories: Occurrence or Claims-made.

- Occurrence policies cover the insured physician against claims arising from an event that took place during the policy period—regardless of when the claim is reported. The date of the incident triggers coverage. If a claim is made several years after the alleged incident and the insured’s coverage is no longer active, the physician would still be covered if the policy was in effect on the date the incident occurred.

- Claims-made policies cover the insured physician for claims reported during an active policy period and which are related to incidents that occur on or after the retroactive date of the coverage policy. The date it is reported triggers coverage. If your policy expires and a claim arises after the expiration date, the insurance provider is not obligated to provide coverage (unless tail coverage [see below] has been purchased Unique concepts related to claims-made policies include:

- Retroactive Date: eliminates coverage for claims produced by wrongful acts that took place prior to a specified date, even if the claim is first made during the policy period.

- “Tail” Coverage: extends your ability to report a claim even after your claims-made policy is cancelled. It is said to “cover your tail” after you leave, and should extend up to 20 years. If you have claims-made malpractice coverage, you will be responsible for paying for tail coverage when you leave. This can have a substantial cost depending on your type of practice and the duration of employment. It is a good idea to purchase tail coverage for any moonlighting done during residency as well.

- “Prior Act or “Nose” Coverage: extends your ability to provide coverage for unknown and unreported claims that occurred prior to the effective date of the policy.

Typical liability policies consist of the following components and should be reviewed carefully—and also, if appropriate, with legal counsel:

- Declarations Page: Summary of coverage outlining entities covered, effective dates, policy type and coverage limitations, and other key information about the insured.

- Limits of Liability: Specific dollar amounts covered by a policy, including the maximum amount per incident and an aggregate amount for the policy period (typically one year). Minimum malpractice liability coverage requirements vary from state to state. Example: A $1 million/$3 million limit of liability means the maximum amount of coverage per incident is $1M and the maximum for all incidents during the policy period is $3M.

- Exclusions: Certain actions, such as specific procedures and locations, not covered under the policy. Additionally, violations of law or ethical standards are excluded, such as physicians practicing under the influence of substances or if a patient overdoses on a medication the physician was not authorized to prescribe.

- Conditions: Restrictions in coverage that impact scope of medical practice, often geographic or procedural, limiting performance to only those for which physicians are properly trained and qualified.

- Endorsements: An amendment to the liability insurance policy that provides additional coverage or adds additional exclusions. For instance, it may add additional coverage that otherwise would be excluded.

Getting Hired

Getting Hired

Now that you have some ideas of what you are looking for in your future practice, the types of practices and compensation models, and the various parts of typical contracts, you are ready to begin putting together your CV (or updating it).

a. Developing a Professional CV

A curriculum vitae (CV) is a common document in medicine. This term is often (incorrectly) used interchangeably with the term resume when talking about future employment. Curriculum vitae literally means “course of life,” implying a detailed recounting of one’s activities. There are a few key differences between a resume and a CV:

The most important difference is the last one: PURPOSE! A resume is used to apply for a job, highlighting how you are the ideal candidate for that position by providing the employer with relevant details about your experience and education. Your CV, on the other hand, is where all this great information should come from; it is a list of experiences, achievements, and awards that you’ve acquired over the years of your life.

A CV usually looks a lot less “flashy” compared to a standard resumé. However, it should still be easy to read, reference, and expand upon. To achieve that, most CVs are divided into sections. Each of these can be formatted in various ways, but the preferred is reverse chronological order: the most recent material is listed first. For prospective employers, those entries are often the most relevant because they identify the job you plan to transition from. You hope an employer will see something on your CV that resonates with them, prompting interest.

With any CV or resumé, language choice is important. Focus on specific achievements and provide as many details as possible. For physicians, these may include, for example, specific scope of practice, how many patients or procedures per week or month, how many hours volunteered per month, how much money the grant provided, etc. There are also specific verbs that better clarify your work and add variety:

- Planned → Developed, designed, organized, prepared

- Directed → Coordinated, guided, managed, negotiated

- Executed→ Achieved, assembled, modified, produced

- Advised → Advocated, demonstrated, illustrated, informed

The major headings you should include in your CV:

1. Training:

- Education: List, in reverse chronological order, all degrees, academic majors and minors, educational institution and location.

- Post-Graduate Education Training: Common formatting “rules” suggest you include your intern year separate from your residency, even if completed at the same location. However, this approach is not written in stone: in family medicine, it is generally a “given” that the two locations are the same

- Professional Development Activities: These are experiences that confer informal education certificates (in addition to your formal education); certificates that are not formally granted or nationally recognized. Examples include communication courses and workshops in a particular skill set, even without a national recognition, such as suturing, colposcopy or dermoscopy.

- Certifications: These are the big ones: American Board of Family Medicine Diplomate, Fellow of the American Academy of Family Practice, and any subspeciality board certifications. Always include dates conferred—which also helps you remember when to renew!

- Medical Licensure: Status, eg, active, inactive, temporary; State awarding the license; and Date obtained are all helpful inputs here, especially when applying for traveling jobs or telemedicine positions.

2. Employment History:

- Clinical Activities: This section contains most of what people think of in a resume for employment history. The most recent activity should be listed first, with dates (including months) from starting year to completion. The description should include anything you find helpful, but we recommend: Setting (inpatient, outpatient, etc.), Role (Physician provider, Attending Physician overseeing residents, etc.), Patient Volume (estimated). It can also include things like the percentage of FTE (full time equivalent), which is the number of half days out of 10 converted to a percentage.

- Academic Appointments: Dates, Academic Rank (e.g., clinical instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), and Organization (eg, Harvard, MIT, University of Kansas).

- Professional Society Memberships: Dates and organizations. This section can be rolled into Local/National service, if desired, but memberships are often useful in and of themselves, delineated from position.

- Honors and awards: Dates and awards. In contrast to your resume, your CV might include other details such as how many were considered, the requirements, etc.

3. Service:

- Institutional: Positions that you held outside of your primary role. This might include committee memberships, initiatives that you lead, activities in which you represented the department. These listings benefit from specific details.

- Local/National Service: This includes any positions you held within broader organizations, like the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM), American Medical Association (AMA), etc. Once again, specific descriptions of the job, your achievements, and the lessons learned are helpful to recall when talking to employers!

- Community Service: This is one of the many places where family medicine shines! Community service can include local outreach and participation in community initiatives (like volunteering at a free clinic), offering medical coverage for sports teams, or publishing medically informative articles in the local newspaper. Again, for the CV you should include specific details: hours volunteered, games covered, etc.

4. Teaching and Mentorship:

This is generally stratified by experience level (e.g., MS-1, Resident) with discrete educational experiences. You can include any presentations, classes, lecture series, or clerkships you taught or facilitated. For those going into academics, you can also include mentorships if you are advising individuals or groups of learners. This annotation also serves the dual purpose of remembering who they were and keeping in touch with them for the years to come! This section may be more limited for residents, especially if you are not going into academic medicine.

5. Research:

- Publications:

In AMA format, list any peer-reviewed articles or book chapters that you’ve authored (in reverse chronological order) Example: Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:638–45.

This list of peer-reviewed articles is followed by any non-peer reviewed works, such as books and educational materials, cited the same way. In your personal notes, you should discuss your experiences and what role you played in authoring the work. As your illustrious career continues you may forget these details.

- Lectures: If you’ve been invited to speak at a professional conference, you should include the date, name of the conference and lecture, and the location. You should keep personal notes about how many attendees were there, if the lecture appeared to be well received, and where you are saving the lecture slides (in case you want to offer it again). Grand rounds, mentored cases, or journal clubs, expected as part of the residency, are generally not included Example: Lipton RB, Reed M. Managing Migraines: What’s New? Lecture at American Academy of Family Physicians Family Medicine Experience. September 2016, Philadelphia, PA.

- Abstracts & Other Works: This can be a place to catch important projects, such as abstracts and poster presentations, although those can also be listed in their own section, as well as any other presentations, eg, a conference presentation regarding research or other educational topics.

- Peer Reviewing: Often journals and other bodies to which you may have submitted content will reach out and ask you to provide peer review for others. Tracking the review dates and journals is important, especially if you’re a subject matter expert.

Summary

The best recommendation for creating a CV is this: start your CV now, with whatever you have! You most assuredly had a well-documented CV when applying to medical school and to residency. That’s a great place to start, and it’s vital to keep up periodically throughout your career with updates. Also, you may be asked to submit a CV for a new opportunity (like a leadership position) unexpectedly! It’s always easier to keep it updated once you start the process and template. Additional resources can be found at the ACP and AAMC:

a. Professionalism: Besides your CV and resume, you should extend professionalism to other areas of communication before seeking a new job. We will discuss social media for practicing physicians in more detail in future units. Below are some basic tips for the interview and hiring process:

- Social Media:

- Be aware that most employers, including educational institutions and residency programs from which you are graduating, have a social media policy. Additionally, most state boards follow guidelines by the Federation of State Medical Boards. It is important to practice these guidelines.

- We recommend you thoroughly review your publicly accessible social media profiles and blogs and determine what you would want a future employer to see. It may seem unfair that what you do in your spare time would have an effect on your professional life. However, unfortunately, it is possible that previous posts, including text, blogs, links, “likes,” profiles you are “following,” photographs and videos, can have an adverse effect on you and your future organization’s reputation.

- Depending on the particular social media platform, you can change past posts to “private” or delete old posts en masse using external web engines. Even deleted posts may be archived on some social media sites or may be discoverable on internet archiving websites; however, even archives can sometimes be deleted with additional steps. While most employers will not engage in investigation to this level, you do want to appear professional and be aware of any professional liabilities.

- You may want to update personal social media accounts so they do not use your full name, reference employers, or educational institutions. This allows you more privacy and is also useful for avoiding being “friended” by employers, patients, colleagues, staff or learners. Additionally, understand how to limit sharing and adjust your friend list to make sure you are only sharing personal information with those who you wish to have access. That said, recognize that anything posted should be considered publicly accessible.

- Develop a LinkedIn and Doximity profile that includes a professional looking headshot. Consider a professional Twitter account. For more information on developing a professional presence, see “Transitioning to Practice.”

- Email:

- You will likely lose access to your educational email. If you use a personal email address for job searches, include a professional name, eg, JimSmith97@gmail.com and not SexyLuvr@yahoo.com. You may even want to have a separate personal email address only for professional interactions, medical websites, etc., for example: JamesSmithMD@gmail.com. Just make sure that you will check it regularly. If you use the account associated with your residency, be aware that you may lose access shortly after graduation.

- 3.Phone

- Include your full name in a professionally toned voicemail message, in case someone needs to leave a message.

- Use a Google Voice or similar phone account to put on job boards and to share with recruiters. This number can be abandoned later, since you will most likely receive A LOT of phone calls from recruiters. Once they have your number, it is likely to be sold to other recruiting agencies and you may continue to receive voice and text messages for years.

b. Recruitment and Job Search:

Hopefully, you now know what type(s) of position you are looking for, so you’re ready to go looking! This section focuses on strategies for searching out and successfully landing your first job out of residency (or to find a better match than your current position).

There are several ways to find a hiring practice:

- Ask your network. Your network consists of alumni, current faculty from both your residency and your medical school, professional connections, and mentors. The people in these groups generally have your best interests at heart. Be aware that, if they respect you, they too may try hard to recruit you directly, making it difficult to say no. However, most will understand if you are truly uninterested in a particular opportunity.

- Use online physician forums and your social media accounts. You may be recruited hard by desperate physicians looking for help, but in general, you will not be spammed with endless job offers.

- Post on a job board and let others reach out:

-

- a. LinkedIn

- b. AAFP CareerLink: Family Medicine Jobs

- c. Nomad Health

- d. Family Medicine Careers: Home

- e. NEJM Career Center

- f. 9437 Physician / Surgeon Jobs

- g.Indeed

- h. Zip Recruiter

- i. For academic careers, also consider:STFM Job Board, Inside Higher Ed, Higher Ed Jobs

You may also seek a professional recruiter. Many residents are pursued by recruiters from intern year with phone calls, pages, texts, emails, and mailings. Your personal information is, unfortunately, sometimes sold to recruiters or available on LinkedIn, making it hard to separate your professional and personal lives. Be aware that there are essentially three kinds of recruiters:

- Recruiters employed by a health system and often financially incentivized to recruit doctors to come to their health system.

- Recruiters who work directly for you and reach out to health systems with your specifications. These recruiters typically work for third party medical staffing firms and utilize contingent agreements, meaning they charge employers, (clinics, hospitals, and health systems), a contingent fee when you sign a contract or on your first day of work.

- Recruiters who represent clinics, hospitals and health systems through third party medical staffing firms to recruit for them. They often work through retainer agreements, charging employers a fee to begin the search and receiving additional fees when you sign a contract or on your first day of work

It is wise to analyze the motivations of recruiters. Some are highly professional and ethical. Others may be unscrupulous or face such heavy pressures to recruit physicians that they begin to misrepresent opportunities. If you partner with a recruiter, you are allowing him or her to serve as an extension of you and therefore represent your character and ethics. A competent, ethical, and professional recruiter will guide you through the process, including organizing interviews and contract negotiations.

Pros of Recruiters:

- They can screen potential opportunities, only presenting ones that align with your personal mission, vision, and values.

- Some recruiters may serve as an advocate for you, helping you negotiate contract terms.

- They may provide updated compensation averages (Medical Group Management Association, etc.).

- Their advertisements are one avenue to learn about new opportunities.

- They can help arrange your interviews.

Cons of Recruiters:

- Some of them are downright annoying and persistent.

- You may be offered a lower salary or bonus if your employer had to pay a recruiter to find you.

- Not all recruiters are honest about the opportunities they are presenting.

- If they do not invest the time and energy to learn about you, they may misrepresent your character and motivations to employers or fail to prioritize your best interests.

NOTE: Just because there is a beautiful picture on a recruitment flier with a golf course does not mean that is what the community will look like! They also often post a picture from the nearest large city, which could be hours away. Additionally, the compensation, benefits, and schedule mentioned on such advertisements are almost never reflective of the contract you would be offered.

Consider carefully how much you want to interact with recruiters. If you choose to interact with one, plan for the following:

- Be completely candid and honest about your skills and preferences.

- Check in regularly with your recruiter to know if things have changed.

- Be upfront regarding where you are and are not willing to go.

- Consider having a Google Voice phone number to share with recruiters. You can always delete the number if its use becomes overwhelming.

d.Interviewing Tips

This may be your first professional interview outside of medical school or residency. In many ways, these interviews are much easier since you don’t have to “prove” yourself. You’re no longer competing with hundreds of other highly qualified candidates for a limited number of positions. Instead, you are a rare and valuable asset. The process of interviewing is more for mutual benefit to discern if the position is a good fit for both you and the practice.

1.Research the Location